.png)

Picture this: you wake up, check your iPhone for messages on WhatsApp, scroll through Instagram, search for something on Google, order breakfast through a food delivery app, and stream music on Spotify during your commute. Before 9 AM, you've already accessed services that would have been impossible just two decades ago – instant global communication, access to virtually any information, seamless commerce, and entertainment tailored to your preferences.

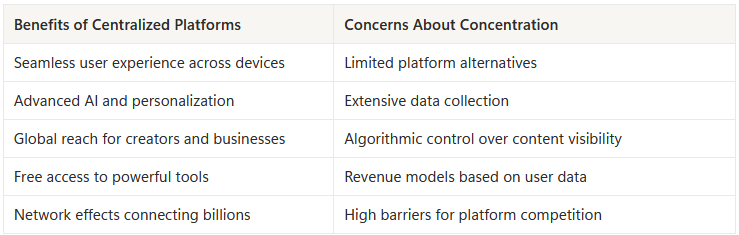

This digital transformation has brought undeniable benefits: small businesses can reach global markets through Amazon and social media, creators can build audiences without traditional gatekeepers, and consumers enjoy unprecedented convenience and choice. Yet this same technological revolution has created an unexpected outcome.

The Web 2.0 Trade-off: Convenience vs. Control

What is platform capitalism? Platform capitalism represents a business model where tech companies control digital infrastructure and extract value by facilitating interactions between users, while accumulating data and charging fees for access to their networks, essentially becoming intermediaries in nearly all digital economic activity.

The concentration of digital power has reached unprecedented levels. Amazon Web Services controls 31% of the global cloud computing market, Microsoft Azure holds 25%, and Google Cloud commands 11% – together, these three American companies control 67% of the world's cloud infrastructure (Chatzistavrou, 2024). This isn't just market dominance; it's control over the fundamental infrastructure that powers the modern economy. In this article, you'll discover how major tech companies have transformed from innovative disruptors into dominant platform operators, and why this concentration of power raises important questions about digital freedom and economic democracy.

The Rise of Digital Feudalism: From Innovation to Domination

The transformation from competitive capitalism to platform feudalism (platform feudalism describes a digital economy where users and creators depend on dominant tech platforms that control access, data, and profits, much like peasants relying on feudal lords.) began after the 2008 financial crisis, when central banks flooded markets with cheap capital through quantitative easing. This influx of capital enabled tech companies to operate at substantial losses while building significant market positions, according to industry analysts (Varoufakis, 2024).

Uber exemplifies this approach. When it launched, Uber charged rates that resulted in losses on virtually every ride. Thanks to favorable financing conditions, it could continue operating at a loss while competing with traditional taxi services. Once it achieved market dominance, Uber adjusted its pricing structure and transformed into a profitable platform business.

This pattern appeared across the tech industry. Amazon offered expedited shipping services while investing heavily in logistics infrastructure. Google and Facebook provided free services while developing comprehensive data collection capabilities. Each company followed a similar strategy: use available capital to gain market position, then monetize once dominance was established.

The numbers reveal unprecedented concentration. The five largest tech companies – Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, and Meta – collectively hold market capitalizations exceeding $10 trillion. Apple alone, worth $3.41 trillion, commands more value than the entire German stock market (Hovenkamp, 2024).

Unlike traditional companies that controlled specific products, major tech companies have achieved significant control over digital infrastructure itself. Amazon operates both as a retailer and as the marketplace where other businesses operate. Apple manufactures devices and controls the App Store through which software is distributed. Google provides search services and operates the advertising infrastructure that funds much of the internet.

This infrastructure control creates what economists call "platform advantages" – the ability to generate revenue by controlling access to digital platforms. When Apple charges fees on App Store purchases, it's monetizing access to iPhone users. When Amazon charges sellers for enhanced visibility, it's monetizing access to customers at scale.

Critics argue this creates a digital economy that concentrates power in ways that may limit competition. Small businesses and individual creators operate within these digital ecosystems, but the major platform operators own the infrastructure and collect significant portions of the value generated. Some economists suggest this represents a shift from traditional market capitalism toward what they term platform-based business models.

The foundation of major tech companies' business models relies significantly on user-generated data. Every click, scroll, like, and search generates information that feeds algorithms designed to predict and influence behavior. This creates what some economists call "data-driven business models" that operate differently from traditional market mechanisms.

The scale is considerable. With 5.52 billion internet users — about 68% of the world's population — generating vast amounts of data daily, the volume of behavioral information being collected is unprecedented (ITU, 2024). Unlike traditional labor arrangements, this data generation occurs as users engage with platforms for their own purposes. Users access services they perceive as free while their usage patterns become valuable business intelligence.

The relationship creates what some analysts describe as asymmetric information control. Users generate the data but typically have limited visibility into how it's processed, who accesses it, or how derived value is distributed. Internal company documents from various tech firms have revealed that algorithms may prioritize engagement-driving content because user engagement correlates with advertising revenue generation.

This data concentration creates network effects that can make market entry challenging for new competitors. Larger user bases generate more data, which can improve algorithmic performance, potentially making platforms more attractive to additional users – creating what economists call self-reinforcing market dynamics.

The impact on users is significant rather than negligible. This asymmetric power dynamic can limit user autonomy and meaningful choice, as individuals have little control over how their data generates value while facing fewer viable platform alternatives due to network effects. Users may also experience algorithmic manipulation of their information environment without full awareness, as engagement-optimized content shapes their digital experience in ways that prioritize platform revenue over user well-being.

Major tech platforms' revenue models depend significantly on capturing and monetizing user attention. Platforms employ design features informed by behavioral psychology to maximize user engagement. Features like continuous content feeds, notification systems, and algorithmic content curation are designed to encourage frequent platform usage.

Research indicates the average person interacts with their phone dozens of times daily and spends multiple hours viewing screens. While individual usage patterns vary, these engagement levels reflect the effectiveness of platforms designed to capture and hold user attention for advertising purposes. This design approach contributes to "doom scrolling" behaviors, where users compulsively consume content feeds driven by intermittent variable reinforcement schedules that mirror addictive mechanisms. Studies suggest excessive screen time and compulsive social media use correlate with increased anxiety, depression, and sleep disruption among users.

When platforms influence what billions of people see and engage with, they potentially affect the information environments that shape public discourse. Events like the 2016 election discussions, COVID-19 information sharing, and various viral content phenomena demonstrate how algorithmic content distribution can have broader social implications.

Major technology companies have achieved significant control over global digital infrastructure, which raises important questions about market concentration and governance. The smartphone ecosystem shows notable concentration patterns, with Apple's iOS and Google's Android powering over 99% of smartphones globally, while both companies operate the primary app stores through which mobile software is distributed.

Social media presents another area of concentration. Meta's platforms reach over 3.7 billion users monthly – nearly half of humanity. Combined with other major platforms, these services serve as primary channels through which billions receive news, communicate, and access information. This level of influence over global information flows raises questions about media diversity and democratic discourse.

This concentration means that a handful of companies now effectively control the digital public square, with the power to shape what information billions of people see and how they communicate – a level of influence over human discourse that arguably exceeds that of any traditional media or government institution in history.

This concentration has created entities that make decisions affecting billions of users while operating according to corporate policies rather than democratic oversight. When platforms modify content policies, adjust algorithms, or restrict access to services, these decisions can have significant political and social consequences.

Platform content moderation operates according to corporate guidelines rather than legal frameworks subject to democratic accountability. While companies maintain appeals processes, these function according to business policies rather than legal standards established through democratic institutions. This creates situations where fundamental rights considerations become subject to commercial interests and corporate policy decisions. For example, when platforms suspend political figures' accounts or restrict content about sensitive topics like health misinformation, these decisions can influence public discourse and democratic processes while being made through internal corporate procedures rather than transparent legal processes with public oversight.

The influence extends beyond content moderation to information infrastructure itself. Search engines process billions of queries daily, significantly influencing what information people can access. Social media algorithms determine what news content billions of users see. These platforms don't merely reflect public opinion – they help shape it through algorithmic content curation systems.

The concentration of digital infrastructure control raises important questions about market dynamics and democratic governance, but solutions are emerging. Decentralized technologies like blockchain, peer-to-peer networks, and open-source software provide technical foundations for alternatives to highly concentrated platform models. Countries like Estonia have developed digital identity systems that give citizens greater control over their data. The European Union's Digital Markets Act represents regulatory attempts to encourage platform interoperability and address anti-competitive concerns.

Most encouragingly, we're seeing the development of platforms that prioritize user sovereignty over data monetization. These emerging models demonstrate that digital services can potentially be provided while better protecting user privacy and maintaining more democratic oversight. The challenge lies in scaling these alternatives and addressing the network effects that tend to favor established platforms.

This is where QANAT's approach becomes particularly relevant. Rather than demanding users abandon familiar digital experiences, we're building infrastructure that combines the convenience of Web 2.0 with the user sovereignty of Web 3.0.

What We Do Differently:

QANAT creates decentralized identity and data infrastructure that puts users in control without sacrificing usability. Instead of forcing people to choose between convenience and privacy, we enable both through:

How We Bridge Web 2.0 and Web 3.0:

Traditional Web 3.0 approaches often require users to manage complex technical systems. QANAT maintains the smooth user experience people expect while running on decentralized infrastructure. Users interact with familiar interfaces – messaging, social features, content sharing – but their data remains under their control through cryptographic ownership rather than corporate terms of service.

Preventing Re-centralization:

The biggest risk for any decentralized system is gradually becoming centralized again. QANAT addresses this through:

What You Can Actually Do with QANAT:

Rather than abstract promises, QANAT enables concrete capabilities:

Our Vision:

We're working toward digital infrastructure that serves human flourishing rather than corporate extraction. This means technology that enhances user agency, strengthens communities, and enables innovation without concentrating power in the hands of a few platform operators.

Just as ancient qanats enabled communities to thrive by giving them direct control over water resources, modern digital infrastructure should enable human flourishing by giving people meaningful control over their digital lives. The technology exists – what's needed is building systems that serve user needs rather than primarily enabling data extraction.

The internet today may be dominated by a small number of large platform operators, but this doesn't have to remain the case. The same innovative spirit that created the internet can create new models of digital organization that serve democratic values and user sovereignty.

The choice isn't between accepting current concentration levels or abandoning digital convenience – it's about building infrastructure that delivers both user control and seamless experiences. By choosing alternatives like QANAT and supporting technologies that prioritize user agency over platform dependency, we can build the foundation for genuine digital freedom that bridges the best of Web 2.0 and Web 3.0.

The future of the internet depends on our collective commitment to reclaiming meaningful control over the digital infrastructure that increasingly shapes our lives, communities, and economies.

If you want to dive deeper, QANAT demonstrates how decentralized identity systems can return data sovereignty to individuals and communities, creating sustainable alternatives to Big Tech's extractive model.